Sherman Genealogy - Dartmouth - Hartford Courant - Letters and Photos

Item #674

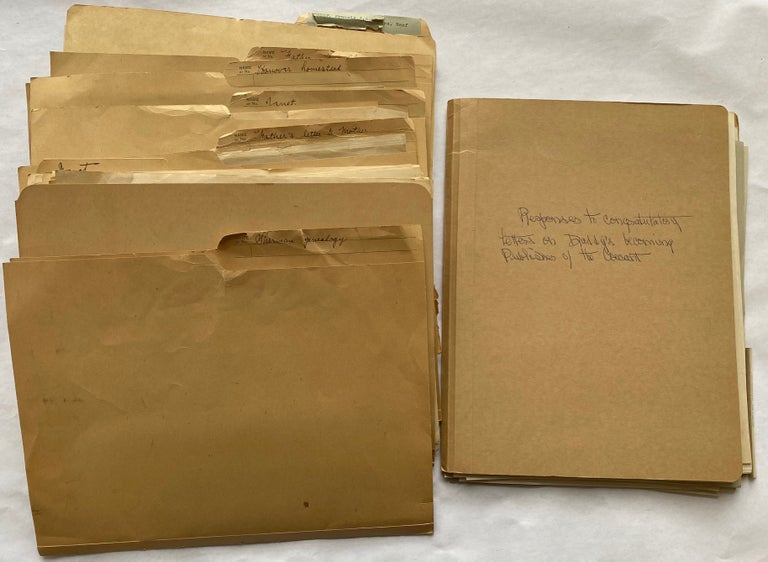

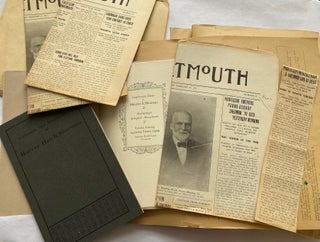

This collection consists of 7 manila folders which are housed in a transparent pink plastic folder with snap closure. The material relates to the Sherman family, including items from Maurice Sinclair Sherman, who became Publisher of the Hartford Courant in 1944. The 7 manila folders are labeled as follows:

● Sherman genealogy

● Father’s letter to Mother

● Janet

● Hanover homestead

● Father - F. A. Sherman

● NEEF, Francis J. A. & Mrs. Neef

● Daddy’s letters to Janet

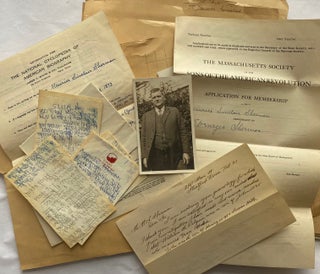

The overall collection consists of around 5 black and white photo postcards, snapshots and mounted photos of Will H. Sherman, the Hanover house and another residence. These photos measure between 4.5 x 3.5” and 8.25 x 6.25” and are loose within the folders.

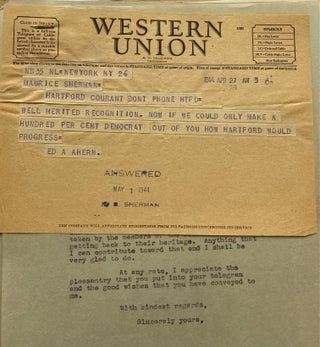

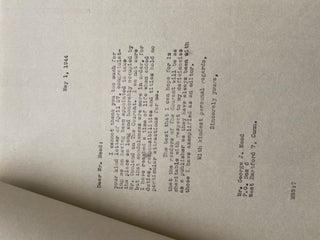

The majority of the collection is made up of upwards of 150 letters, many of which seem to have been written by Maurice Sinclair Sherman, to his daughter, Janet, and his sister, Mrs. Francis Neef, and to the friends and colleagues who congratulated Maurice on becoming publisher of The Courant in 1944. Because of his work, there are also several newspaper clippings that show Maurice at work, as well as an amusing clipping showing him fishing in Berkshire with former President Calvin Coolidge.

This collection also contains handwritten notes detailing the genealogy of the Doten/Dotey/Doty family from the 1620s to the 1800s, booklets on the ancestors and descendants of Hatch Sherman compiled by Frank Asbury Sherman in 1913, and an application by Maurice, as a descendant of Ebenezer Sherman, for membership to The Massachusetts Society of the Sons of the American Revolution.

Letter from Francis Asbury Sherman to “Darling Lu” (Worcester, Mass., Oct., 1870

My Darling Lu:

I propose now to give you a condensed outline of my personal history as I promised in my last letter I would do soon. If you should consult the old family Bible which used to lie in state upon the parlor table at the old Homestead, you would find that Francis Asbury Sherman was born Oct. 4, 1842.

There preceded him Augustus Addison and Adelaide Affina, and he was followed about two years later by Frederic Milton.

As I intend to speak only of myself, I will dismiss the others with the remark that they are all married and settled in life — the older brother is now living in Wisconsin, the younger in Great Falls, N. H., and the sister in Liberty, Maine.

Said Francis or (as he was always called and now subscribes himself) Frank is the son of Harvey H. and Eliza D. Sherman, for whom he has always had the greatest love, reverence and respect.

Arriving at an age when boys begin to take note of their surroundings he found himself the son of a farmer in comfortable circumstances, yet who believed, nevertheless, that hard work and plenty of it was the best occupation for a boy, in which belief, though he then thought it rather Puritanical, he most heartily concurs. He was remarkable for nothing particularly in those days that he can now remember, so the days of boyhood can be passed over without further comment. Father was a farmer in summer and a schoolmaster in winter. He held various town offices of trust, settled business affairs for his neighbors, was a prominent leader in all religious and educational matters, and on the whole a very useful and worthy member of society.

Mother was an angel of mercy always. The sick and sorrowing never appealed to her in vain. She was always ready to go at every call, when her own duties made it possible, even though her own health suffered in consequence. I used frequently to attend her (much against my own will I confess) on expeditions of this kind when no earthly good could be accomplished, except gratify some old woman’s whim. To my expostulations she would sometimes answer, “Now my dear boy, supposed the poor soul should die; could I ever forgive myself for not going to see her when she wants me so much?” Of course there was nothing more to be said.

She was a wonderful manager at home, and with all the demands made upon her time and strength by others, none of us ever lacked anything she could supply. So much for my ancestors, paternal or maternal.

Father’s absence in winter threw the care of the stock and out door matters generally on my shoulders. Fred used to divide the work with me, but the responsibility was mine. After I was twelve and he ten, our regular work, in winter, was to do the chores (as we call it) and go to school a mile and a half from home. Of course we were obliged to be up early and late in order to get any school advantages at all. Like Paul, I used to feel in those days as though I had on me the care of all the churches.

When I was fifteen, Father thought he could not do for us children all he would like to do with the proceeds of the farm, having a brother in Wisconsin who strongly advised him to go there and engage in trade, he did so, mortgaging the farm and stock to raise the necessary means.

All went well with him and with us at home for the next two years, during which time I was farmer in chief. I worked with a will for I supposed in a few years, at most, I should have an opportunity to gratify my thirst for knowledge, and the thought nerved me to constant effort.

But my hopes were doomed to disappoint. Trade at the West was overdone, and Father, with hundreds of others, went down before the great financial crash of 1856-7. But, unlike many others, he was too honest to save anything for himself out of the ruins, as he might have done. (For which all honor to him.)

He came home the following Spring several thousand dollars poorer than when he went away, and of course my dreams of school and college fled with the lost dollars. The money lost had been risked partly for my benefit, and it was now clearly my duty to do what I could to restore it. My brother Augustus, who went to Wisconsin with Father, remained there, and is, I believe, doing well. At home we now all bent our energies to one object; viz. to get out of debt.

We bought additional land, and commenced operations on a larger scale, and had the satisfaction of seeing our incumberance slowly but surely passing away. So the time passed until 1860 – the beginning of the war. Up to this time my school privileges had been exceedingly limited, but with two terms of school away from home, I had managed to pick up knowledge enough to enable me to teach a common school. The winter of 1860 was one of the pleasantest I remember. We were beginning to see the way out of our financial embarrassments – Father was teaching in our district, and I in an adjoining one and boarding at home, and though the weekly Tribune brought us ominous reports from the South, in common with most others we never supposed anything would really come of all their brag and bombast, or, at least, anything that would disturb the peace and quiet of our little circle.

But how little we know of the future! I went away to school in the Spring, and, while away, Fort Sumpter fell and the war was really upon us. I wrote immediately for permission to join the army. In a few days Father’s reply came, which, while it approved of my purpose in general, counselled delay. The need of men was not pressing, for more were offering themselves than could be accepted, and while such was the case those who were so much needed at home as myself, he thought, ought not to go. If, however, the time should come when the country should stand in need of such as I, he would not say nay.

This accompanied by Mother’s earnest entreaties, for the time prevailed, and after the term closed I went home and began my regular summer duties upon the farm. The war news in general, the success of our arms and our prospects of final victory, were topics of constant discussion during the summer, both at our work and in our leisure hours. In all these duscussions entire devotion to country and the Union of all the States was the universal sentiment. Father sometimes doubted our ability to put down the Rebelion, but Fred and I, owing probably to greater ignorance and the ardor of young blood, were always perfectly confident. Mother seldom had anything to say, except to hope that it would all be settled somehow before we should be obliged to go – a sentiment universal with all the Mothers of the land. But when the time came to make the sacrifice, no Mother of them all more readily admitted its necessity, or with purer devotion to the cause of Fatherland laid her sons upon the altar. First, came a letter from the West announcing that Augustus had joined the Wis. Cavalry; and a little later Fred, without consulting any of us, privately enrolled himself.

I was now the only boy left, and although the war fever ran high in my veins, I resolved that until the need of men became more pressing, from purely filial motives to remain at home. The call for 300,000 men after the disastrous campaign on the Peninsular in the Summer of 1862 made it necessary for such as could not very well be spared from home to step to the front, and among those who responded to the call was myself. Being anxious to go into active service at once, I joined the 4th Regt. Maine Vols., then doing duty with the army of the Potomac. I found the Regt. at Alexandria, Va., a few days after the second battle of “Bull Run”, and a more forlorn looking set of men, I venture to say, could not be found outside the Army of the Potomac.

The company to which I was assigned had nine men fit for duty, or who were called fit, but to me they seemed much more fit for the hospital.

On the whole, the prospect was not flattering for a new recruit. It is not necessary for me to say much concerning my period of service. The more important facts you are already acquainted with. Suffice it to say – my name stands free from any stain upon the Adjutant General’s Report: and that I was three times wounded – once at Fredericksburg, and twice at the Wilderness, one of which wounds resulted in the loss of my arm, and of course caused my discharge from the service. My whole period in the army from the date of enlistment to date of discharge was about two years and eight months.

I reached home in the Spring of 1865 in time to be with poor Mother during part of her last illness, which was a great comfort to us both. I found myself now at the age of 23 with one arm and a capital of $500 (the savings of my soldier life) with which to make my way in the world. It was, and still is, a great trial to be left one handed, and I feel it more keenly than anyone but myself knows. But I have never shed any tears over it but once, and probably never shall be guilty of doing the like again.

I did not enter the army with the expectation of leaving it without scars. I counted the cost fully, and went because I believed duty called me.

I have never seen any reason to think differently, and under similar circumstances, I have no doubt I should do the same thing again. Therefore, why should I spend time in bewailing my unfortunate condition?

Better by far to make the best of it, and trust the issue to God. But this is a digression.

It became a serious matter with me to know what to do. I determined to try an experiment. The army had not entirely destroyed my fondness for books, and in order to find out whether I had still enough love for study, and ability enough to pursue a course with success, I took an elementary work on Algebra, with which I had previously had some acquaintance, but which seemed then like a new science, and began its study in sober earnest.

If I could complete it, unaided, there was some hope; if not, then not much.

It was not a very easy matter, but in about three months I laid down the book in triumph. I assure you no victory before nor since ever seemed half so sweet. I now declared my intention of investing what little capital I had in education, and for that purpose went to Bucksport Seminary, where I was when the war broke out, and entered myself as a student. My plan at first was to spend two years there, and endeavor to fit myself to teach the better class of common schools or for a bookkeeper, or Govt. Clerk, or something of the kind. But after being there one term and measuring myself with other young men who were going to college, more ambitious thoughts began to possess me.

If they could go to college why should not I? The only difficulty seemed to be to secure the necessary funds. Father thought it was a great undertaking, still if I was anxious to try he would assist me what he could. With this assurance, after remaining a year at Bucksport, during which time I got along cheaply, for the greater part of the time boarding myself, I went to Hanover. What has transpired since you know. I have not allowed Father to make his assistance a free gift as he wished to do, but have given my notes at various times for what I have received from him. I desired to be independent, if possible, and as I was of age, he was under no obligation to furnish me with means, hence to accept money, as a gift, would simply be accepting charity, a thing I am too proud to do. The amount of these notes is $457.59, besides the interest, the greater portion of which debt I shall be able to discharge the present year. Father’s pecuniary circumstances have much improved. All incumberance upon the farm was removed six years ago, and two years ago he leased it to his brother for ten years with the proviso that if during that time he should be paid the sum of $3500 and interest the property should pass from his hands to his brother’s. Father is now 62 years of age, robust and vigorous, though owing to tender feet, unable to endure farm labor. As you know, he is now living in Bangor, and is engaged in insurance.

If fortune smiles upon me my home will be his when he wishes to retire from life’s active duties. I trust I shall be able to make his last days cheerful and happy, so that he may regard them as truly his best.

Now, my Dear, you know (if you have had patience to read all this) the principal facts in my history. I have endeavored to state them just as they are, without adornment of any kind.

I fear, however, that I have represented my own part in this little autobiography in a more favorable light than it deserves; if so, you must ascribe it to the natural egotism of the race in general, and not to any deliberate intention of doing so. It is all very much condensed, as to go into details would take too much of my time and yours. If, however, there are any points upon which you desire further information you have only to mention them and you shall be fully satisfied. You doubtless have noticed that I have made no mention of any love affairs; but the reason is a good one – I have never had any until now, and of the rise and progress of this you are thoroughly informed. I had, I suppose, about the usual number of schoolboy flirtations, everlasting friendships and all that, but nothing more, and with this avowal I close the chapter.

Letter from Santa Claus to Janet

Dear Janet.-

I asked your Daddy to write this note to you. There is a real Santa Claus and he is found in the hearts of those who love you, just as Mother and Daddy and Nana all love you. That is why they have tried to make this a pleasant Christmas for the dear little girl who herself has a kind and loving heart. If she was not such a nice girl we should not want to do so much for her. We all hope the New Year will be the best and happiest you have ever had, that you will do your best in school and try to improve your opportunities in every possible way.

See you again next Christmas.

Lovingly yours

Santa

Dec 24, 1928

Midnight.

P.S. I must hurry; my reindeers are waiting for me

S. C.

Letter from Maurice Sherman to Francis Neef (March 3, 1943)

Dear Francis:

Dr. Walter R. Steiner who long practiced in Hartford and was known throughout the country as one of the best authorities on the history of medicine, died recently and among his effects is a picture of Daniel Webster on his deathbed surrounded by such prominent men of the time as Clay and Choate. The picture is done is colors from a painting made by Joseph Ames and it is mounted in a heavy, well-preserved gilt frame, four feet by three feet.

It has occurred to Dr. Steiner’s three maiden sisters that possibly Dartmouth College would like to have this picture for its Webster collection and if so, they would be glad to donate it, provided only that the small cost of packing and shipping it is borne by the college.

Can you let me know as soon as possible if the college would welcome this gift? I say as soon as possible because the Misses Steiner have sold the house and want to get everything out of it as soon as they can.

I saw the picture this morning and unless the college already has a duplicate of it, I feel sure that its possession would be worth while. I am sorry to trouble you about this matter knowing how busy you are in these trying days, but I know where to go when I want to get action.

It is snowing here again this morning, just as I was hoping for an early Spring. If my oil ration coupons are to hold out Spring cannot come any too soon or be any too warm. Confidentially, I have just had a tip that the No. 5 coupon will be available for use March 6, and that it will be good for the original ten gallons instead of the eight to which the coupons were cut.

We have thus far got through this worst of all winters—worst here in Connecticut at least—pretty well, although we are still without a maid and day help is almost impossible to obtain. I hope everything is going well with all of you.

Sincerely yours,

[unsigned].

Sold